By: Juliana Sopko

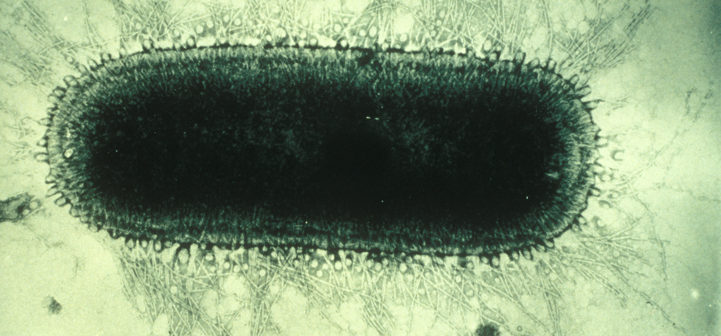

Image courtesy of Norden, a Smith-Kline Company; CC-BY-SA 4.0.

Vaccine hesitancy is an issue that has lingered in the fringes of US society for many years. However, with the emergence COVID-19 and subsequent development of the COVID-19 vaccine this attitude has spilled into the mainstream. Now a new startling trend has been picked up by veterinarians, vaccine hesitancy amongst pet owners. A recent study conducted by Boston University and published in the journal Vaccine found that around 53% of US respondents who are dog owners have concerns over the safety and efficacy of the rabies vaccine1.

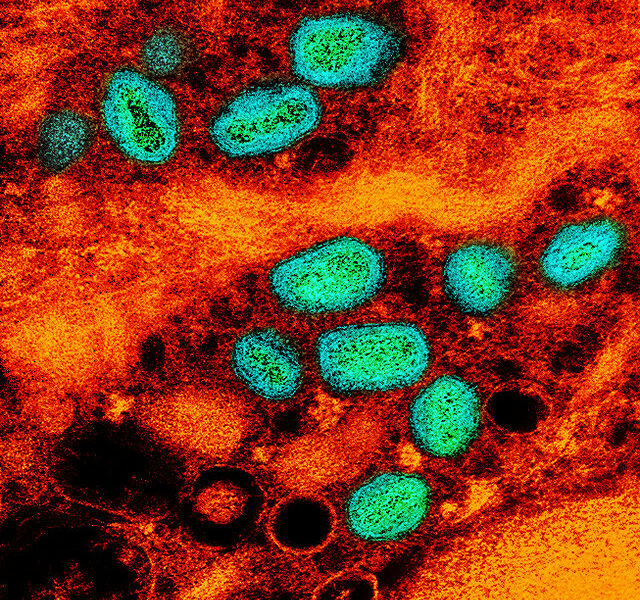

Rabies is a zoonotic viral disease caused by a type of Lyssavirus which is found in various animal species throughout the world. It is most commonly contracted when an animal or human is bitten by an infected host. It is believed that all mammals are susceptible to the rabies virus, and it has been found on every continent except Antarctica. Once transmitted the virus travels along the victim’s peripheral nervous system (PNS) and then enters the central nervous system (CNS). It is within the CNS that the virus replicates before it travels back to the PNS and infiltrates other tissues, including the salivary glands2. According to the Mayo Clinic once an individual or animal begins to show signs of infection it is almost always fatal. The first symptoms of illness present similarly to the flu and may linger for many days. However, later signs are more concerning and unique, such as vomiting, anxiety, excessive salivation, fear brought on by attempts to drink water, fear brought on by air blown on the face, and hallucinations.3

For centuries, rabies presented a very real public health threat for communities. Louis Pasteur, a French scientist and father of pasteurization, set out to create a vaccine to help fight back against this scourge. He developed a 14-dose series using rabbit spinal cord suspensions that contained progressively inactivated rabies virus. He conducted animal trials on dogs and after four years of experimentation found a formula that was consistently successful in animal subjects. In 1885, Louis Pasteur administered his vaccine to his first human patient, Joseph Meister, a 9 year-old who had been bitten by a rabid dog. The immunization was successful and spurred rapid adoption of immunization globally. By the turn of the 19th century rabies treatment centers had sprung up in many cities across the globe like Budapest, Florence, Shanghai and Chicago.4

Animals have been safely vaccinated against rabies for over 100 years. There are various iterations of the vaccine intended to prevent rabies in animals including modified live vaccine, inactivated rabies vaccine, and oral modified live vaccine.5 Just like in humans animals can experience mild symptoms after vaccination such as mild fever, decreased appetite, and discomfort at the vaccination site.6 Successful vaccination has been a major win for global public health leading to significant decline in morbidity and mortality caused by rabies.

Despite this fact it appears that a sizable proportion of pet parents have a distrust in animal vaccination. According to articles by the Washington Post and NPR many pet parents have never seen a rabid animal. However, the individuals interviewed had seen or heard stories of animals acting strangely after receiving a vaccine.1,6 It is important to note that all current research on this topic has been qualitative and opinion based. Only time will tell if these attitudes translate to action and result in an increase in rabies infection.

Sources

- Huang, Pien. “Vaccine Hesitancy Affects Dog-owners, Too, With Many Questioning the Rabies Shot.” NPR, 11 Oct. 2023, www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/10/11/1205016558/canine-vaccine-hesitancy-dogs-rabies.

- “Rabies | CDC Yellow Book 2024.” CDC.gov, wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2024/infections-diseases/rabies#:~:text=Numerous%2C%20diverse%20lyssavirus%20variants%20are,from%20rabies%20occur%20each%20year.

- “Rabies – Symptoms and Causes – Mayo Clinic.” Mayo Clinic, 2 Nov. 2021, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/rabies/symptoms-causes/syc-20351821.

- Historical Perspectives a Centennial Celebration: Pasteur and the Modern Era of Immunization. 5 July 1985, www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00000572.htm

- “What to Expect After Your Pet’s Vaccination.” American Veterinary Medical Association, www.avma.org/resources-tools/pet-owners/petcare/what-expect-after-your-pets-vaccination.

- Bever, Lindsey. “More Than Half of U.S. Dog Owners Are Skeptical of Canine Vaccinations.” Washington Post, 29 Sept. 2023, www.washingtonpost.com/wellness/2023/09/22/dog-owners-vaccine-hesitancy.