Worldwide attention has recently been brought to the disease called Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1, or HTLV-1. News outlets have been reporting that indigenous populations of Australia are experiencing startlingly high rates of infection – with up to nearly 40% of their population infected [4]. While this extreme prevalence is stark, it is not actually a new issue. HTLV-1 has thus far predominantly been affecting small populations around the world [5], ranging from south-western Japan, the Caribbean, Guyana, among others [8]. However, these clusters have failed to be featured in headlines due to small overall populations that are largely made up of marginalized communities. The rate of HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 infection in the U.S. is small, but notable, at 22 per 100,000 [1].

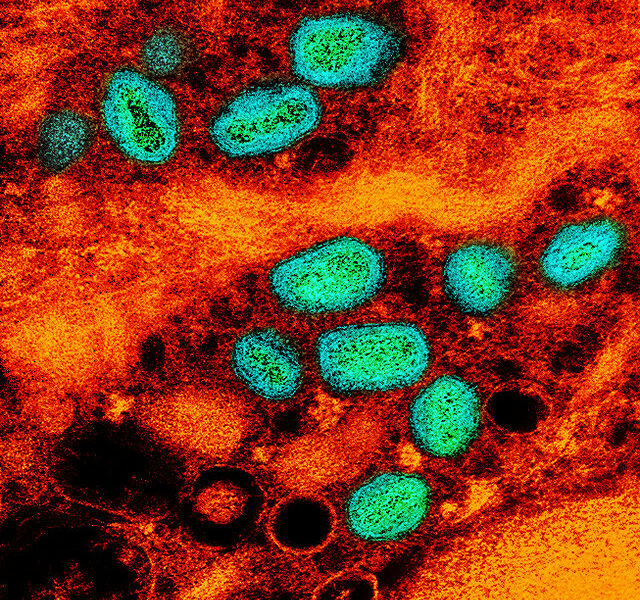

HTLV-1 is a retrovirus [6] that affects the T-cells of the immune system in humans [2]. While the majority of people infected will not develop symptoms from the infection, possible complications include: Adult T-cell leukemia (ATL), HTLV-1 associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP), or other medical conditions [2]. Of people with HTLV-1, 2-5% will develop ATL, and 0.25-2% of people with HTLV-1 will develop HAM/TSP [2].

HTLV-1 was originally isolated and detected in 1979, from the analysis of a T cell line established by J. Minna and A. Gazdar from a patient these clinicians called a cutaneous T cell lymphoma [9]. While literature discussed HTLV-1 shortly in the 1980s, little research has actually been done to accurately assess the prevalence of HTLV-1 and investigate treatment and prevention options [1]. While the virus was only recently discovered, DNA tracings of HTLV-1 were found on a 1,500-year-old mummy in South America [4]. Due to lack of attention, little funding has been allocated to create a vaccine or provide better treatment options for those who are infected. The virus has largely been overlooked, in part because it overwhelmingly affects marginalized communities.

HTLV-1 is similar to HIV in its genetic makeup, and often is deemed the “cousin virus” of HIV [3]. While people become infected in nearly identical ways, mainly including blood transfusions, IV drug use, and sexual contact, 95% of people infected with HTLV-1 remain asymptomatic their entire lives [2]. In addition, HTLV-1 does not spread as easily as HIV [3]. Women have higher reported rates of HTLV-1 infection, and the prevalence of infection dramatically rises with age [1].

Within the United States, HTLV-2 is more common than HTLV-1 [1]. HTLV-2 is very similar to HTLV-1, and is contracted the same way. Most infected people also do not develop any symptoms during their lifetime, however, the potential complications from infection differ from HTLV-1, in that HTLV-2 is associated more with neurological problems and lung conditions [7]. Complications include sensory neuropathies, gait abnormalities, bladder dysfunction, cognitive impairment, and motor abnormalities [7].

HTLV-1 is an example of how a disease among marginalized populations can go decades with minimal science or media. Due to the recent attention to the virus, and the extensive work that has been done on HIV treatment, health practitioners are optimistic that progress will be made in reducing the transmission, and improving treatment, of HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 in the near future.

Sources:

[1] https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/209/4/486/2193425

[2] https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/9645/human-t-cell-leukemia-virus-type-1

[3] https://www.livescience.com/62502-htlv-1-australia.html

[4] http://www.businessinsider.com/what-is-htlv-1-hiv-like-virus-spreading-australia-2018-5

[5] https://www.cnn.com/2018/05/07/health/htlv-1-virus-australia-explainer/index.html

[6] https://www.baker.edu.au/research/laboratories/infection-chronic-disease/project-htlv1-survey

[7] https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/9783/human-t-cell-leukemia-virus-type-2

[9] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC555587/