‘Tis the season for the obligatory “best of” lists for 2014. We thought we’d take a look back at some of this year’s notable diseases and outbreaks. Our list has been limited to the nice round number of ten. Does this list seem representative of 2014 to you?

1. Avian Influenza – H7N9 (China)

Over the last year, Avian Influenza H7N9 has continued to emerge and spread in parts of Asia. According to the WHO, Avian Influenza A virus subtypes circulate in bird populations and have been detected in the past. However, Avian Influenza H7N9 had not previously been detected in animal or human populations prior to 2013 [1]. In March 2013, China reported its first human cases of H7N9 and as of December 22, 2014, there have been 454 confirmed human cases of H7N9 including numerous outbreaks in both human and bird populations — all across China, with imported cases to Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Malaysia [1,2,4]. Contributing factors to H7N9 infection include previous exposure to poultry or potential infected environments, including markets in which infected poultry may be sold [2,3]. What makes H7N9 a concern is its symptomatic manifestation — with most cases developing respiratory distress, including severe pneumonia, which may then result in death [4].

Nevertheless, it is essential to note that while there is evidence for limited human-to-human transmission, it does not seem that there is sustained human-to-human transmission [4].

[1] http://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/h7n9-virus.htm

[2] http://outbreaknewstoday.com/china-reports-seven-new-human-cases-of-h7n9-avian-influenza-85173/

[3] http://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/h7n9-virus.htm

[4] http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/phn-asp/2013/h7n9-0403-eng.php

2. Influenza (United States)

The 2013-2014 influenza season in the United States, which peaked in the last week in December 2013, was predominated by the influenza A, H1N1 strain. This strain is best known for being the source of the 2009 H1N1 Swine Flu pandemic. Following the influenza A peak in December, influenza B illnesses lingered into the spring of 2014, particularly effecting the Northeast [1]. The 2013-2014 season of influenza was notable for the population most affected. The CDC reports that approximately 60% of influenza-like-illness hospitalizations were among the 18-64, or young and middle-aged adults, range [2]. Typically though influenza is most severe in the very young, the very old, and those who may have comorbidities.

In the CDC’s mid-season seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness estimates, the 2013-2014 flu vaccine was estimated to be 62% effective against the influenza A H1N1 strain. Due to H1N1’s predominance in the 2013-2014 season, there were not enough influenza B or other influenza A strain viruses to compare for vaccine effectiveness [3].

The National Immunization Survey-Flu (NIS-Flu) and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) collections information on influenza vaccination coverage. For the 2013-2014 season, 58.9% of all children ages 6 months to 17 years, and 42.2% of all adults ages 18 and older were vaccinated. This is the highest rate of vaccinating, for both age groups, in the past five flu seasons. However, there continues to be significant variation in vaccination coverage rates between states [4].

[1] http://www.cdc.gov/flu/pastseasons/1314season.htm

[2] http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/p0220-flu-report.html

[3] http://www.cdc.gov/flu/pastseasons/1314season.htm

[4] http://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1314estimates.htm

3. Ebola (West Africa)

The largest Ebola outbreak in history began in late 2013, when a young boy died in Meliandou, Guinea, a village situated on the border of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone [1]. Alongside weak health infrastructure and limited resources to fight and contain the disease, the virus quickly advanced through the three countries, moving into the capital cities and other key urban centers [1]. According to the CDC, the outbreak has contributed to a small number of imported cases in Nigeria, Senegal, Mali, Spain, and the United States, with all cases considered to be contained [3]. As of December 29, 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports 20,081 cumulative cases worldwide and 7,842 deaths [2].

International response to the outbreak has spanned from funding to field response. Countries, alongside non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have contributed to the building of Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs), contact tracing, as well as medical and non-clinical support teams [5].

Healthcare workers are at highest risk of contracting the disease, as Ebola is spread in human-to-human transmission via direct contact — including infected blood, secretions, and organs, as well as surfaces and materials that may be contaminated with these secretions [4]. Improper or insufficient use of personal protective equipment (PPE) can contribute to the propagation of the virus in healthcare settings.

To review more key events from the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, please visit our Timeline: www.healthmap.org/ebola

[1] http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2014/12/28/the-year-in-ebolahowtostopthenextoutbreak.html

[2] http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.ebola-sitrep.ebola-summary-20141229?lang=en

[3] http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/

[4] http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs103/en/

[5] http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/12/02/fact-sheet-update-ebola-response

4. MERS (Saudi Arabia)

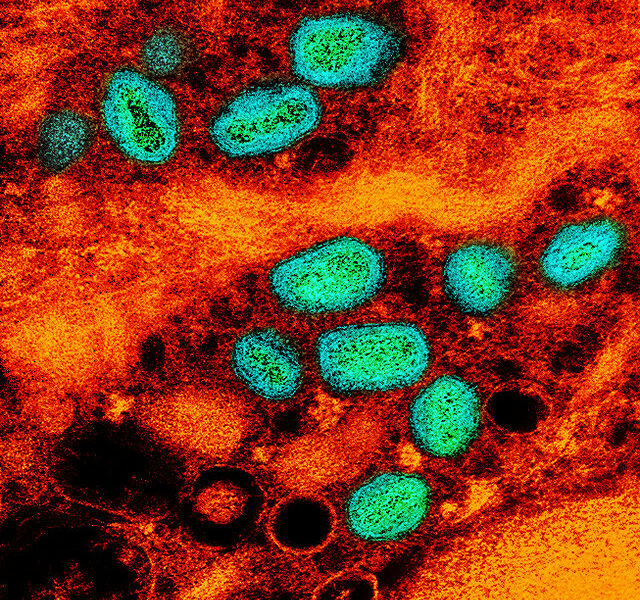

MERS-CoV, or Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome, is a novel coronavirus first reported in 2012 in Saudi Arabia. MERS cases have been reported in 17 countries, including the Middle East, Europe, Africa, Asia and North America [1]. All 938 cases and 343 deaths (as of 17th December 2014 reported by WHO), have had direct or indirect links to the middle east [2]. MERS, being a respiratory virus, generally presents with cough, fever, and pneumonia. Asymptomatic or carrier infections have been identified through contact follow-up. The source, and/or route of exposure to the virus remains largely not understood, with some cases having no contact with cases. However, close contact with infected individuals, in families and among health-care workers, has been shown to lead to transmission events. MERS does not appear to be particularly contagious or infectious [3].

In 2014, between the January 3rd and December 17th WHO’s MERS updates, the case count has risen by 761 cases and 269 deaths [4]. This represents a significant surge in case counts since its identification in 2012. This surge in cases began in the spring of 2014, localized to healthcare facilities in Riyadh and Jeddah, Saudi Arabia [5]. Between March 1st and June 30th, Saudi Arabia confirmed 525 new MERS cases [6]. This sudden uptick in cases, twice the number of cases previously identified since 2012, raised significant concern over the upcoming Hajj pilgrimage in October 2014. As a result, substantial precautions and monitoring were undertaken by the Saudi government. No MERS cases were reportedly associated with the Hajj pilgrimage this year [7].

MERS cases continue to be reported, in Saudi Arabia and abroad. The most recent country reporting a new MERS case is Jordan [8]. Over half of all MERS cases have been classified as primary cases, raising questions about sources of exposure or infection [9]. Evidence has been collected demonstrating close contact with camels as a source of human MERS infection [10]. Given the sustained case frequency, continued MERS surveillance and vigilance, especially in healthcare settings, is recommended by the WHO [11].

[1] http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/faq/en/

[2] http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2014/12/news-scan-dec-16-2014

[3] http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/faq/en/

[4] http://www.who.int/csr/don/17-december-2014-mers/en/

[7] http://www.arabnews.com/news/640391

[8] https://en-maktoob.news.yahoo.com/jordan-confirms-mers-virus-infection-case-232218256.html

[10] http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1401505

[11] http://www.who.int/csr/don/17-december-2014-mers/en/

5. Salmonella (United States)

The HealthMap database is set up to pick up alerts involving product recalls with concern over possible Salmonella, or other pathogen, contamination. These products ranged from pet foods to ground oregano. To get a more macro-scale of Salmonella in the United States in 2014, the CDC reported on nine large-scale outbreak investigations. The most substantial, and the only still ongoing investigation, being the multistate outbreak of Salmonella Enteritidis involving bean sprouts. As of December 15th, 111 cases of Salmonella Enteritidis have been identified in 12 states – with 66% of those interviewed reporting eating bean sprouts prior to illness. The investigation continues, and case counts continue to rise [1]. Other Salmonella outbreaks in 2014 were: Salmonella linked to backyard poultry; Salmonella Braenderup linked to nut butter; Salmonella Newport, Hartford, or Oranienburg linked to sprouted chia powder; and Salmonella Stanley linked to raw cashew cheese [2]. For more information on recalled products please see: http://www.fda.gov/Safety/Recalls/

[1] http://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/enteritidis-11-14/index.html

[2] http://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/outbreaks-2014.html

6. Measles (United States)

This year’s record breaking number of measles cases in the United States is the highest it’s been in the last twenty years [1]. It is by far the highest it has been since measles elimination — what the Center for Disease Control (CDC) defines as “the absence of continuous disease transmission for 12 months or more in a geographic area” — was declared in the United States in 2000 [2]. Over the course of the last year, there have been 610 reported cases of measles across twenty states [2]. The reemergence of measles can be attributed, in part, to increased international travel where infected travelers have imported the disease into the United States. Particularly for 2014, many measles case clusters were traced back to the large ongoing measles outbreak happening in the Philippines [2]. However, those in the United States who have become infected are generally unvaccinated, often by their own volition [2,3].

[1] http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/p0529-measles.html

[2] http://www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html

7. Rabies (United States)

Worldwide, approximately 55,000 deaths are attributed to rabies each year. The global death rate is so high because the disease has a nearly 100% mortality rate. Rabies 100% vaccine preventable, yet it remains endemic in 150 countries worldwide [1]. By contrast, between 2003 and 2013, there were only 34 human rabies cases reported in the United States. Of these 34 cases, 10 were reportedly due to animal exposures abroad [2]. The rate of human and animal rabies infection in the United States remains very low, largely attributable to education of the general public and domestic animal vaccination policies. In the United States, the source of most frequent rabies exposure varies by region. The CDC reports on the terrestrial rabies reservoirs in the United States, with skunks predominating the central US, raccoons predominating the eastern seaboard and fox predominating parts of Alaska [3].

Despite the significant media attention that wildlife testing positive for rabies receives, an average of only three human rabies cases occur in the United States each year [4]. Missouri health officials reported a human rabies death this September [5]. The majority of human cases in the United States are a result of contact with a bat [4]. Bat bites can go unnoticed, especially if the bite occurred in a home while sleeping. The best way to prevent rabies exposure is to avoid contact with wild animals and to vaccinate your pets [4].

[1] http://www.who.int/rabies/en/

[2] http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6320a2.htm

[3] http://www.cdc.gov/rabies/exposure/animals/wildlife_reservoirs.html

[4] http://www.humanesociety.org/animals/resources/facts/rabies.html

[5] http://outbreaknewstoday.com/missouri-officials-investigate-human-rabies-death-99851/

8. Chikungunya (United States)

Chikungunya, a mosquito-borne virus transmitted by the same Aedes mosquito that spreads Dengue virus, reached the Caribbean and subsequently, the United States, earlier this year [1]. Derived from the Kimakonde language, Chikungunya means “to become contorted” and aptly depicts the “stooped appearance” of those infected by the virus with severe joint pain [2]. Previous identification of Chikungunya in the United States have been from travelers visiting or returning to the United States from endemic or affected areas [3]. This year, however, eleven locally-acquired, or ‘autochthonous’, cases have appeared in Florida [3]. This may contribute to increased locally-acquired cases within the United States in the future [3].

[1] http://www.cdc.gov/chikungunya/pdfs/Factsheet_Chikungunya-what-you-need-to-know.pdf

[2] http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs327/en/

[3] http://www.cdc.gov/chikungunya/geo/united-states.html

9. Whooping Cough (United States)

Whooping cough, a bacterial disease that causes an upper respiratory infection, has dramatically increased across the country over the last year. Notably marked by the deep ‘whooping’ sound it stirs in its victims, whooping cough is highly contagious and is passed through droplet transmission, which happens when a person coughs or sneezes [1]. While a vaccine exists for whooping cough, this year’s outbreaks across the United States have reached a significant number of cases. Between January 1 and August 16, 2014, the CDC reported 17,325 cases of whooping cough across 50 states — this number would be an increase of 30% compared to the same time period in 2013 [2].

One of the hardest hit states this year was California, where outbreaks and cases were the highest they have ever been in the last 70 years [3]. Between January 1 and November 26, 2014, California reported 9,935 cases of whooping cough — a conversion of 26 cases per 100,000 people for that time period alone [3]. Infants have been impacted the most by the epidemic and efforts to ensure the vaccination of pregnant women have been increased to provide conferred protection to babies [3].

[1] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0002528/

[2] http://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/outbreaks/trends.html

10. Enterovirus D68 (United States)

Enteroviruses, which are responsible for infecting up to 15 million Americans per year, generally do not cause symptoms in those infected. This genus of viruses also includes Rhinoviruses and Polioviruses. However, a rarely seen species of the virus, Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68), has been causing severe respiratory illness in children in the United States in 2014. From August to December 18th, 1125 cases of EV-D68 were confirmed across 49 states, including suspected involvement in 12 deaths [1]. As with many other illnesses, confirmed case counts may be substantial underestimates because individuals with mild illness may not seek medical care.

EV-D68, being a predominantly respiratory virus, presented in affected individuals with generally mild cold symptoms. Individuals with underlying conditions, particularly children with asthma, were at higher risk of more severe symptoms/infection. Of greater concern though is that the severe symptoms did not end there. Between August 2nd and December 10th, there have been 94 CDC-confirmed reports of what is not being called “Acute Flaccid Myelitis” – or paralysis – associated with EV-D68 infection in children [2].

It remains unclear why 2014 was such a particularly bad year for EV-D68, an otherwise rare disease. Other viral infections, such as West Nile Virus and Adenoviruses, have been known in rare cases to infiltrate and damage the central nervous system. Medical professionals and epidemiologists do not yet know why EV-D68 may be causing these paralysis symptoms. It is undetermined if paralysis-linked EV-D68 is as rare and only-recently seen as described. This uncertainty is due to EV-D68’s rarity and lack of a ‘track-record’. The good news is, though, that the illness seems to be on the decline.

[1] http://www.cdc.gov/non-polio-enterovirus/outbreaks/EV-D68-outbreaks.html

[2] http://outbreaknewstoday.com/more-enterovirus-acute-flaccid-myelitis-cases-reported-in-the-us-90602/