West Africa’s Ebola outbreak continues to grow. In Guinea, as of April 9, the World Health Organization reports 158 cases and 101 deaths. Liberia has reported 20 suspected cases and five laboratory confirmed cases of Ebola, as well as 12 suspected deaths. The two suspected cases reported in Sierra-Leone have been laboratory confirmed as Lassa Fever, and despite media reports of a case in Kumasi City, Ghana, laboratory testing has ruled out Ebola. In Mali, two of the six suspected cases have tested negative for Ebola while testing is ongoing for the remaining four. On April 7, the WHO’s Epidemic & Pandemic Alert and Response published a Dashboard for this particular outbreak that shows the breakdown of cases per country, district, age group and gender. You can check their site for more situation updates.

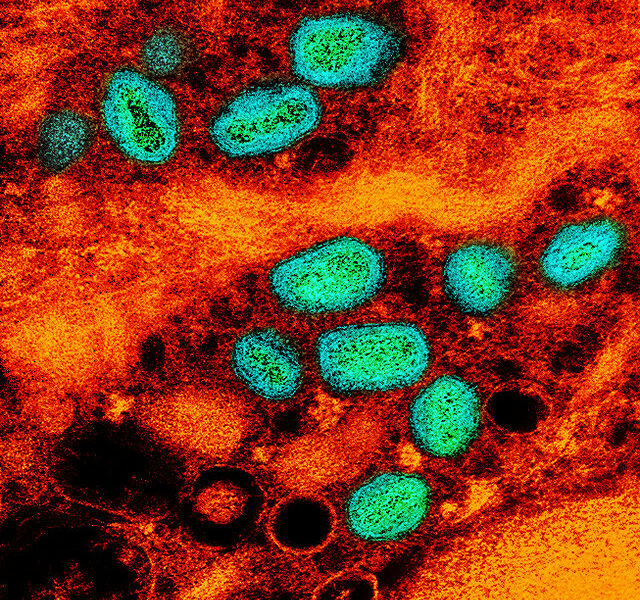

In the event that we have some new visitors, here is a little bit of background on Ebola and how it is believed to be transmitted. Ebola is a zoonotic pathogen in the Filoviridae family (Marburg virus is also in this family). The reservoirs of filoviruses have remained unknown for decades, though research published in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases in February 2013 suggests fruit bats as a likely source. Transmission of Ebola has also been documented through contact with infected wild animals such as chimpanzees, gorillas, monkeys, antelope, and porcupines.

So, an outbreak of Ebola typically begins with an infected wild animal. One or more humans have contact with blood or other fluids from the infected animal, sometimes during the hunting or preparation of bushmeat. The virus spreads through human-to-human contact primarily in healthcare settings, households, and funerals. In this particular outbreak, the WHO reports that 15 of Guinea’s cases are in health care workers (ten have been laboratory confirmed, and five are probable cases). During traditional funeral ceremonies contact with bodily fluids is common as family members clean and prepare the body for burial typically without any personal protective equipment. A 1996 outbreak of Ebola in Gabon began with 18 hunters who skinned and consumed a chimpanzee found dead in the forest. Five of the hunters died, and many others became ill after attending a traditional funeral ceremony.

A 2011 article by the Center for International Forestry Research reports that animals such as deer, rodents, antelope, primates, and birds are regularly hunted, and in some areas of the world this bushmeat serves as one of the main sources of animal protein; its consumption is often a means of survival. In Guinea, bats are frequently served in a stew known as “kedjenou,” or dried over a fire, and in Cote d’Ivoire local markets sell bats “stewed or braised” along with pangolin, agouti, and other mammals ready to be cooked.

Officials in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia have banned the sale of bushmeat in local markets in an effort to stop the spread of Ebola. Reuters reports that some specialists remain skeptical about the ban’s effectiveness as many depend on bushmeat for protein and income. Further, some are not convinced that smoked or cooked bushmeat is a significant source of Ebola infection. In late March, Reuters spoke with a virologist and hemorrhagic fever specialist, Bob Swanepoel, who stressed that filoviruses are transmitted by infected animals and “fresh carcasses” rather than cooked or smoked meat.

In a statement on Tuesday, April 8, Dr. Keiji Fukuda of the WHO stated that the current outbreak could last for months. Health officials in West Africa continue to track contacts of sick individuals.

Dr. Thomas Yuill, a moderator for ProMED-mail and Professor Emeritus in the Department of Pathobiological Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison spoke with me about the challenges that exist with the current Ebola outbreak. Dr. Yuill has a joint PhD in wildlife ecology and in veterinary science with a specialization in virology. He has worked throughout the world in the field of zoonoses.

AH: Are you aware of any challenges specific to the current outbreak?

TY: The thing that is most challenging about this outbreak is not only that it is in West Africa, where the virus had not previously been seen, but that it is in many different places including Guinea and Liberia, with suspect cases previously identified in Sierra Leone in people that had traveled from Guinea.

Another challenge that exists is catching up with contacts, as the population is spread out and highly mobile. In addition, some of the regions in Guinea did not have reliable maps available, however maps have since been provided so that health authorities are better able to find houses in these hot spot areas and may now begin going house-to-house to identify any missed cases and potential contacts. Tracking and identifying contacts to specific locations is a tremendous task for officials to complete.

Lastly, there is a lot of fear among locals, which is not surprising given the nature of the disease and the high case fatality rate.

AH: Do you think we will continue to see more cases as part of this outbreak, and what can health officials do at this point to stop the disease from continuing to spread?

TY: Authorities will be able to halt the current outbreak with good case finding and contact tracing practices. It is likely that more cases will be seen however, and getting this outbreak halted will not be easy and will take some time.

AH: Could you tell me more about why the reservoir for Ebola has not yet been confirmed?

TY: If Ebola is not highly prevalent in wildlife populations it will take an enormous effort, including costly field studies to track it down. If you are not in the right place at the right time one may not find it.

AH: Do you have any insight about the consumption of bushmeat in these countries, as that is a risk for disease transmission?

TY: The consumption of bushmeat is a well-established practice in many parts of Africa and it constitutes a significant amount of protein for many people as well as a source of income. The ban on bushmeat that has been placed by several countries will likely be extremely difficult to enforce.

AH: Any final thoughts on the ongoing Ebola outbreak?

TY: I think for all of us this has been a major wake-up call. These things can and do happen by surprise and then the challenge is to be ready for them when they occur to be able to respond quickly because the virus isn’t going to wait for us to get organized.