Last week, Bill Gates, co-founder of both Microsoft and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, told the Washington Post that one of the most surprising things he encountered upon entering global health was that “things like the rotavirus vaccine were going unfunded.” No doubt, Bill was pleased to read the news this week. India’s Department of Biotechnology and the pharmaceutical company Bharat Biotech announced positive results from their recent clinical trials for Rotavac, an effective new rotavirus vaccine.

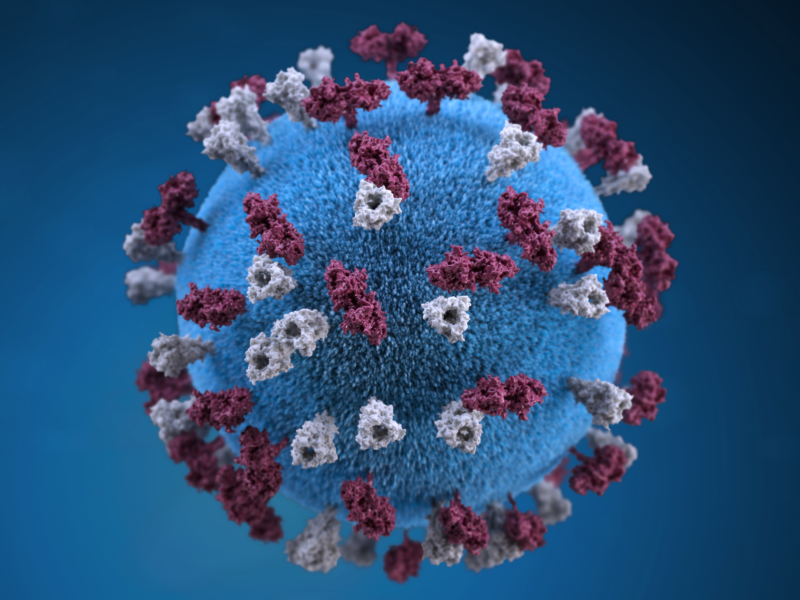

Rotavac is an attenuated vaccine, meaning the component that spurs our immune system is a weakened form of the rotavirus. This particular vaccine was made in India for India—the country serves as home to both Bharat Biotech as well as 20 percent of the annual rotavirus deaths worldwide. Even the weakened virus component used in the vaccine was derived from a strain isolated from an Indian child in New Delhi in 1985.

According to the trials, Rotavac reduces the chance of severe diarrhea by more than half for one year. Over the next year, the protective effect persists, but begins to wane.

The Need for a new Vaccine

Rotavirus is the most common cause of severe diarrhea in children. Every year, over half a million people die from the virus—85 percent being from developing countries.

One might think that rotavirus, like cholera and other diarrheal diseases spread by fecal-oral contamination, would be all but eliminated by a water and sanitation system. However, rotavirus is tougher than that. The bug was a persistent threat in the United States until 2006. At that time, the CDC estimated that the virus infected every single child before their fifth birthday.

So what changed in 2006? That year, Merck introduced Rotateq, an oral rotavirus vaccine that costs $10.50 for a three dose series. A couple of years later, GlaxoSmithKline released Rotarix, a two-dose oral vaccine that costs $5 for the full series. In the United States, Rotateq and Rotarix became part of the standard vaccine package for children. However, in rural India, the cost was too much. Rotavac works because it will cost less than $3 for the series of three doses and was specifically tested with the oral polio vaccine to ensure the two medications do not alter each other’s efficacy. Additionally, Rotavac seems to protect children against all kinds of diarrhea, at least to some extent.

A New Road

The path to developing a cheap and effective vaccine demanded new partnerships. Rotavac in particular was the product of a unique public-private partnership that brought together Bharat Biotech, a private pharmaceutical company, with the Indian Government, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the American CDC, the non-profit PATH, and others. The purpose of the partnership was to combine knowledge while dividing cost. Ostensibly, their plan was a success.

For Bill Gates, the numbers don’t lie, “If you spend the less than 2 percent of what the rich countries spend, but you spend it on vaccinations and antibiotics, you get over half of all that healthcare does to extend life. So you spend 2 percent and you get 50 percent.”

However, the impact of Rotavac may ultimately be more personal. Maybe soon, when Rotavac receives licensure in India, the case of diarrhea kids get from being dirty and playing with other kids will not be a matter of life and death; maybe it will never happen at all.