The emergence of locally acquired NDM-1 in two Canadian hospitals raises concerns about “superbugs” and antibiotics’ future futility.

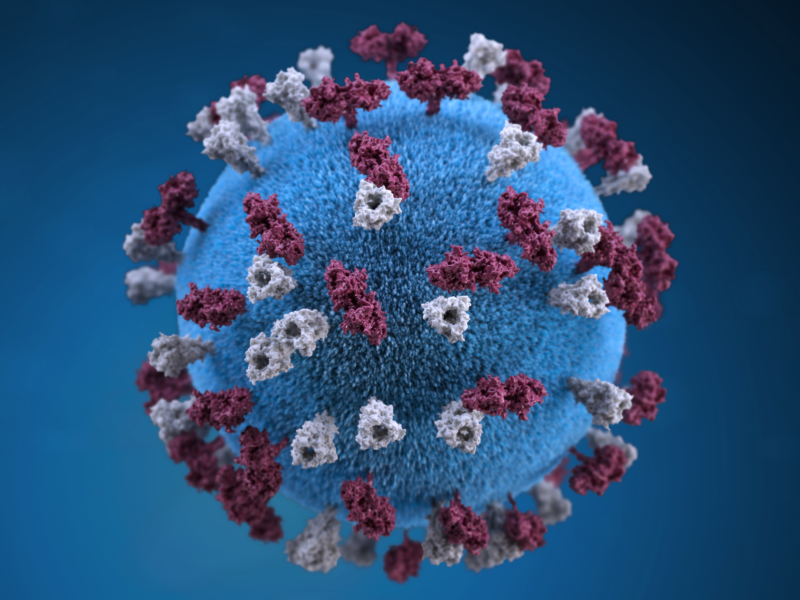

NDM-1, or New Delhi Metallo-beta-lactamase-1, is actually not a “superbug”, but an enzyme produced by certain bacteria that confer antibiotic resistance. Take this analogy for example: spinach is to Popeye as NDM-1 is to Klebsiella pneumonia. NDM-1 provides this infection with the superbug strength to withstand previously effective antimicrobials. Further underscoring the enzyme’s super powers is the ability of the gene responsible for producing the enzyme to spread unhindered between different types of bacteria. This leaves physicians with few but toxic drugs to treat varying infections, such as E. coli and Salmonella.

NDM-1 bacterial strains have been reported in patients globally, all of who had a history of travel or medical tourism to NDM-1 prevalent areas, such as India. However, two recently released studies on outbreaks of NDM-1 Klebsiella pneumoniae (NDM-1- Kp) in two Toronto-area hospitals are the first of their kind to report the emergence of locally acquired infections. Both outbreaks discovered patients who were hospitalized with the drug-resistant bacteria despite no travel history linked to hospitalization or medical treatment in endemic countries.

This drug-resistant version of Klebsiella Pneumoniae spreads quickly and easily in healthcare settings. In the second outbreak, which occurred at the Sunnybrook Hospital in Ontario, it was discovered that the likely source of the outbreak was a shared hand-washing sink. The resistant pathogen spread rapidly from two to seven patients.

Although not all patients carrying the enzyme will develop infections, those that do often suffer from urinary tract infections, blood stream and wound infections, and pneumonia. Few existing antibiotics are able to effectively treat these illnesses. For example, strains exist that are susceptible to only two antibacterial agents, colistin which is associated with high rates of kidney toxicity, and tigecyline, which the FDA recently linked to an increased risk of death.

Surveillance

It is difficult to track and monitor NDM-1 infections. Ideally, a hospital’s infection control team will trace all contacts of the infected patient and test them to see whether they are carrying the organism as well. Unfortunately, this is not always so easy. In the Sunnybrook outbreak, for example, the majority of contacts had already been discharged before they could be tested. Additionally, in some cases, swabs did not come back positive until three weeks after exposure – thus, it is likely that hospitals that do not test this far out will miss positive cases.

On an international level, the National Collaboration Centre for Infectious Disease recommends establishing a coordinated surveillance program to monitor NDM-1 resistance. Pan-resistant strains, such as those that may contain the enzyme, are not currently notifiable to the WHO. A more accurate understanding of NDM-1’s threat to public health and safety could be gained if the emergence of such a strain were reported as a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC).

Other prevention methods

In the healthcare setting, routine contact precautions must always be adhered to. These include hand hygiene, using personal protective equipment (PPE), and proper cleaning and disinfection of all equipment.

Additionally, the overuse of antibiotics in veterinary and human medicine, as well as in agriculture, has fostered the development of antibiotic resistance. Stricter oversight over antibiotic use in humans and animals, and promotion of antimicrobial stewardship are foundational steps towards managing the impending threat of antibiotic futility.