In a special telebriefing on West Nile virus (WNV) in the United States, Dr. Lyle Petersen, director of the Division of Vector-borne Infectious Diseases at the CDC stated that we are “in the midst of one of the largest West Nile virus outbreaks ever seen in the United States.”

This afternoon the Massachusetts Department of Health reported its second human case of WNV this year. Both cases occurred in Cambridge. The WNV threat risk has been raised from “moderate” to “high” in Cambridge, Arlington, Belmont, Boston, Brookline, Somerville, and Watertown. In the press release, Department of Health commissioner John Auerbach states: “Today’s announcement is a compelling indicator that the threat of mosquito-borne illness is widespread, and people should continue taking simple common-sense steps to protect themselves.” West Nile virus has been found in mosquitoes in nine counties in Massachusetts so far. Last year, the state recorded a total of six human WNV cases and one equine infection.

Based on reports from August 21, 47 states have reported infected birds, mosquitoes or humans (Alaska, Hawaii and Vermont remain WNV-free). For this year, there is a total of 1118 human WNV cases and 41 deaths.

Texas, Mississippi, Louisiana, South Dakota and Oklahoma bear the brunt of the outbreak as they report about 75 percent of the total number of WNV cases. Of this 75 percent of cases, Texas reports approximately half, making it one of the hardest-hit states. On August 22, the Texas Department of State Health Services reported 640 confirmed human cases of WNV and 23 deaths. Dallas and Tarrant counties are reporting the most cases in Texas.

In the telebriefing, Dr. David Lakey, Texas commissioner of Health, put the current outbreak into perspective. “[P]rior to this,” he said, “our worst season was 2003, at which time we had 439 cases of neuroinvasive disease and 40 deaths overall statewide.” He then focused on Dallas in particular: “[i]f you look at Dallas County data and add up the total deaths from 2003 to 2011 they had ten deaths. We’re now in this year, [Dallas County has] more deaths than their entire history.”

Texas has set up an Incident Command to facilitate coordination and communication between local, state and federal governments and the public health community. It has also reduced the time it takes to confirm cases. According to Lakey, the state previously did cultures for the virus, and it took ten days to confirm WNV cases. Now, it uses molecular diagnostics and it only takes two days to confirm cases. The “cornerstone” of the response, again according to Lakey, is the collaboration with the media. Through the media, the Department of State Health Services (DSHS) has sent out several public service announcements and advisories on how to avoid mosquitoes and the spraying activities that are going on.

The question seemingly on everyone’s mind is: why is it so bad this year? The answer is: no one really knows. Part of the difficulty in figuring this out, as Petersen reminded listeners yesterday, is that there is a very complicated ecological cycle involving mosquitoes, people and birds. Hot weather, though, has consistently promoted WNV outbreaks.

The question and answer session of the telebriefing indicated that most people were concerned about the types of illness that occur after being infected with WNV.

Perhaps it is time for a detailed look at West Nile Virus.

About West Nile Virus

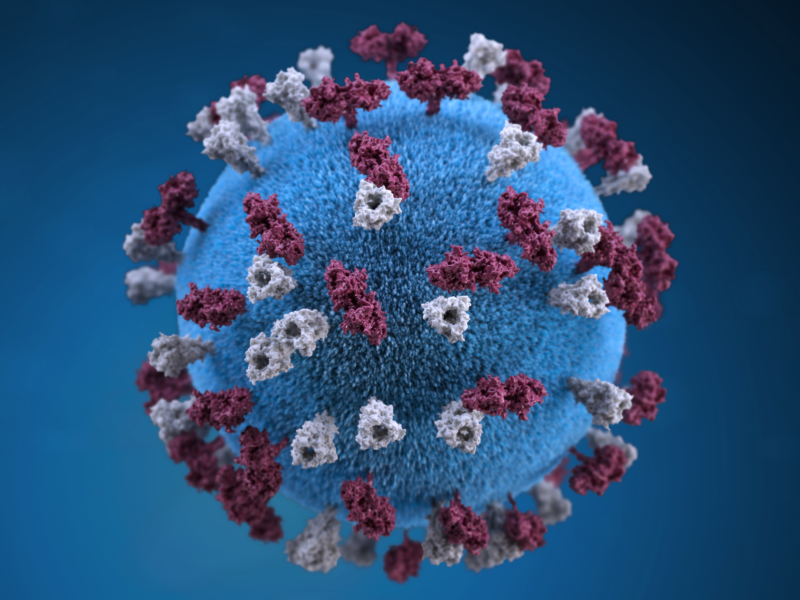

The virus was first discovered in 1937 in Uganda. West Nile Virus hasn't been in the United States for too long; according to the CDC, scientists believe that it surfaced around the summer of 1999. It is a member of the flavivirus family, along with diseases like yellow fever, dengue, and Japanese encephalitis.

The main method of WNV transmission is through mosquito bites. Over 43 mosquito species can transmit the virus, which they do by biting an infected animal or bird, and then biting a human. Cases of WNV usually spike in late August to early September because mosquitoes carry the highest amounts of the virus around this time. As late fall and winter come around, the mosquitoes die off.

Other methods of transmission, though rare, are blood transfusions, organ donations and from mother to child during pregnancy or breastfeeding.

While the numbers reported by the CDC and the Texas DSHS seem alarmingly high, infections are actually underreported because most people do not know they have been exposed to or carry the virus. In the telebriefing, Petersen estimated that maybe only two to three percent of all those who get the milder WNV infections are actually recorded. People with a mild infection (referred to as West Nile fever) experience symptoms like diarrhea, headache, muscle aches, sore throat, rash and swollen lymph nodes. Depending on the seriousness of these symptoms, a person might blame feeling sick to a number of reasons, without ever suspecting WNV. Mild symptoms might last up to a week.

The more serious forms of infection, West Nile encephalitis or West Nile meningitis, are often more striking and therefore reported. These forms can be life threatening. As Petersen explains, West Nile meningitis is an infection of the tissues surrounding the brain. This results in severe headaches, eye pains, stiff necks etc. West Nile encephalitis is an infection of the brain itself and will cause symptoms such as confusion and loss of consciousness. Other symptoms include convulsions, high fever, muscle weakness or paralysis. These symptoms usually occur three to fourteen days after infection, and they can develop very quickly. According to the CDC, about one in 150 people with WNV will develop a serious illness.

There is no specific treatment for WNV infection. Most cases of WNV cure themselves without medical attention. For severe cases, getting medical attention immediately is recommended and it may result in hospitalization.

Because there is no vaccination, the CDC recommends using insect repellent, wearing long sleeves and pants at dusk and dawn (prime time for mosquitoes), having screens on doors and windows, and clearing and stagnant water.

An issue of concern for many is probably where the outbreak will go. Donald McNeil from the New York Times posted this question to Petersen. Southern states, replied Petersen, are affected earlier than the northern states because of weather patterns. But in terms of traveling from one area to the next, “That’s not quite what’s happening. What is happening is West Nile virus is epidemic throughout the United States. You’ll find West Nile virus throughout the continental United States…it’s just a matter of whether enough amplification of the virus is everywhere.” This is the part that is hard to understand- just why the outbreak is more severe in some areas than others.

The CDC is posting updates on WNV case counts and has provided a map that shows the disease burden across the United States in birds, humans and mosquitoes. Additionally, the American Association of Blood Banks has created a West Nile Virus Biovigilance Network that collects data on donors (blood, tissue and hematopoietic progenitor cells) with suspected WNV infection in the United States and Canada. The result is a map that shows suspected and confirmed positive donations in the United States and Canada.